“ Two hundred years after braille’s invention, we are blessed with the ability to convert print into a myriad of formats. All of these alternative formats have their advantages, but I cannot overstate the simplicity, flexibility and equivalent access that braille offers. As Jews we value literacy, and by offering our blind congregants access to ritual texts in braille, we are giving them the best opportunity to participate fully in our community.”

This week, I’m reprinting a blog post I published last year on ReformJudaism.org.

It’s about the importance of braille access in my Jewish life. Although the post focuses on my Jewish experience, it points more generally to the value of braille literacy to participation in many settings, such as religious services, where communal reading is a part of the culture and where technology use can be problematic. Here is what I wrote:

Louis Braille was born in Coupvray, France in 1809. When he was 3 years old, he accidentally poked himself in the eye with his dad’s awl, and became blind. When he was 12, he started playing around with an embossed alphabet that had been used by the military to exchange messages in the dark, and by the time he was 15 he had created what we call braille today. In his short 43 years, Louis Braille brought literacy to a group of people who, up until then, could only read and write using raised print letters-which posed practical challenges. The six-dot code Louis Braille created is simple enough for almost anyone to learn (I would contend, simpler than print) yet elegant enough that it can be written in many languages.

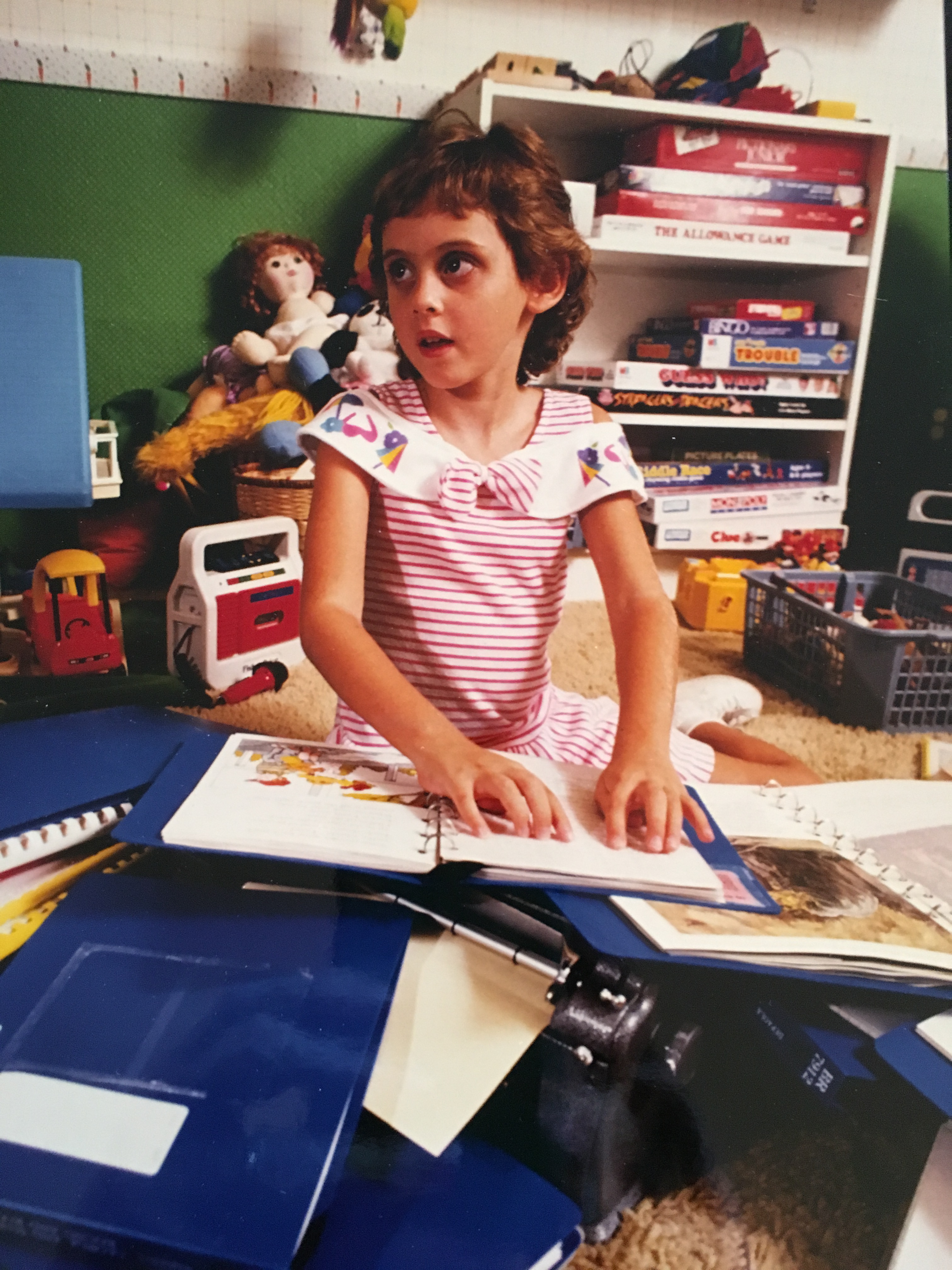

I was born almost completely blind, 150 years after Braille’s creation. My parents didn’t know much about blindness, but they quickly committed themselves to two things: ensuring that their older daughter and I would both love to read, and providing both of us with a strong foundation in Jewish traditions and values. During my preschool years I spent four days a week at a local preschool for blind children where I learned the English braille code, and I spent one day a week at a Jewish day school where I learned to recite Jewish blessings by ear.

When I was about seven years old, my parents ordered a braille Siddur for me from the Jewish Braille Institute (JBI) in New York. When I went to the synagogue with them, I would proudly carry my Siddur, and I tried to read along. But I didn’t yet know the Hebrew braille alphabet. At our synagogue, Hebrew wasn’t taught until the fourth grade, but I begged my parents to teach me so I could participate in services. They didn’t know the code themselves, so they reached out to JBI again and got me a Hebrew braille primer. As it turns out, there is much overlap between the English and Hebrew alphabets in braille, with Hebrew braille written from left to right and only a few new symbols to learn. After I studied my Hebrew primer, I was so excited to go to the synagogue and read all the familiar prayers for myself. Most exciting of all, I could read aloud alongside my family during responsive prayer, and participate in silent meditation.

My Jewish education continued, culminating in my bat mitzvah when I was 13. JBI prepared my Torah portion in braille, and I used braille to conduct the service, read from the Torah and present my prepared Dvar Torah. My bat mitzvah experience was identical to that of my sighted classmates.

Braille is the simplest way for a blind person to read independently, but not everyone promotes its use. Some argue that audio-recorded materials should be used instead, but sighted people have not collectively switched from print reading to audio. There are clear advantages of reading, in print or braille, instead of being read to. Audio recordings and text-to-speech technology have a place in my life, but there is no substitute for braille, especially in the tech-free Shabbat service. Listening to a recording would isolate me in prayer, but with braille, I can pray aloud or read along silently, while still immersed in my prayer community and their voices. Braille gives me the flexibility to interact with the liturgy in the same ways as my fellow Jews reading it visually.

The irony is that technology, sometimes thought to “supplant braille”, actually makes braille easier to produce than ever before. Modern braille printers and digital “braille displays” can place braille at a person’s fingertips in seconds. Digital braille displays make braille more portable than ever before. Braille can be used by people with low vision, the totally blind and those who are deaf-blind, the young and the old. I have known people in their 90’s who learned the braille alphabet after becoming blind in old age. Though producing braille in both Hebrew and English can pose some technical challenges, libraries like JBI have the expertise to make this happen.

Two hundred years after braille’s invention, we are blessed with the ability to convert print into a myriad of formats. All of these alternative formats have their advantages, but I cannot overstate the simplicity, flexibility and equivalent access that braille offers. As Jews we value literacy, and by offering our blind congregants access to ritual texts in braille, we are giving them the best opportunity to participate fully in our community.